CAN O' BEANS

Launched in the year of the Marshall Plan’s announcement, CAN O' Beans circulated in American cities as both staple and signal. Internal memoranda from the Office of Price Administration describe “the smiling can” as a bellwether for post‑rationing demand. In photographs from Truman‑era press tours, the mark appears at the edge of frames—prosaic, steady, emblematic of the promise that household plenty would follow geopolitical reconstruction.

The design language—beige stock, red ring, confident linework—was calibrated for visibility on mixed shelves where wartime packaging lingered. Regional grocers adopted the product as a metric of normalization: when beans in that label moved, the neighborhood was judged “returned.”

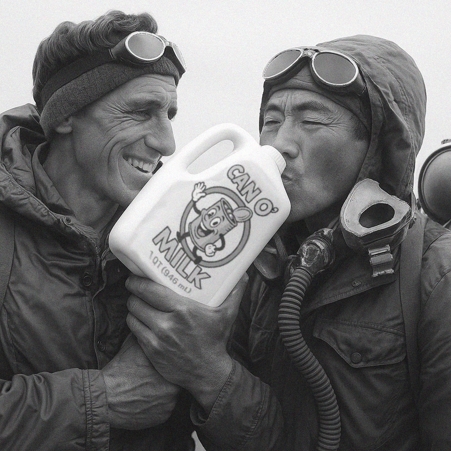

CAN O' MILK

Introduced the summer Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay reached the summit of Everest, CAN O' Milk was framed as an achievement in endurance logistics. Eisenhower’s National Defense Council circulated a briefing on civil‑defense provisioning that cited shelf‑stable dairy as a priority; CAN O' Milk appears in the appendix as a model for distributed storage during transport disruptions.

Trade bulletins from that quarter show unusual adoption by park services and youth expeditions. The label’s vernacular warmth—script tone over field color—positioned the product between farm memory and aerospace pragmatism, a register the decade understood intuitively.

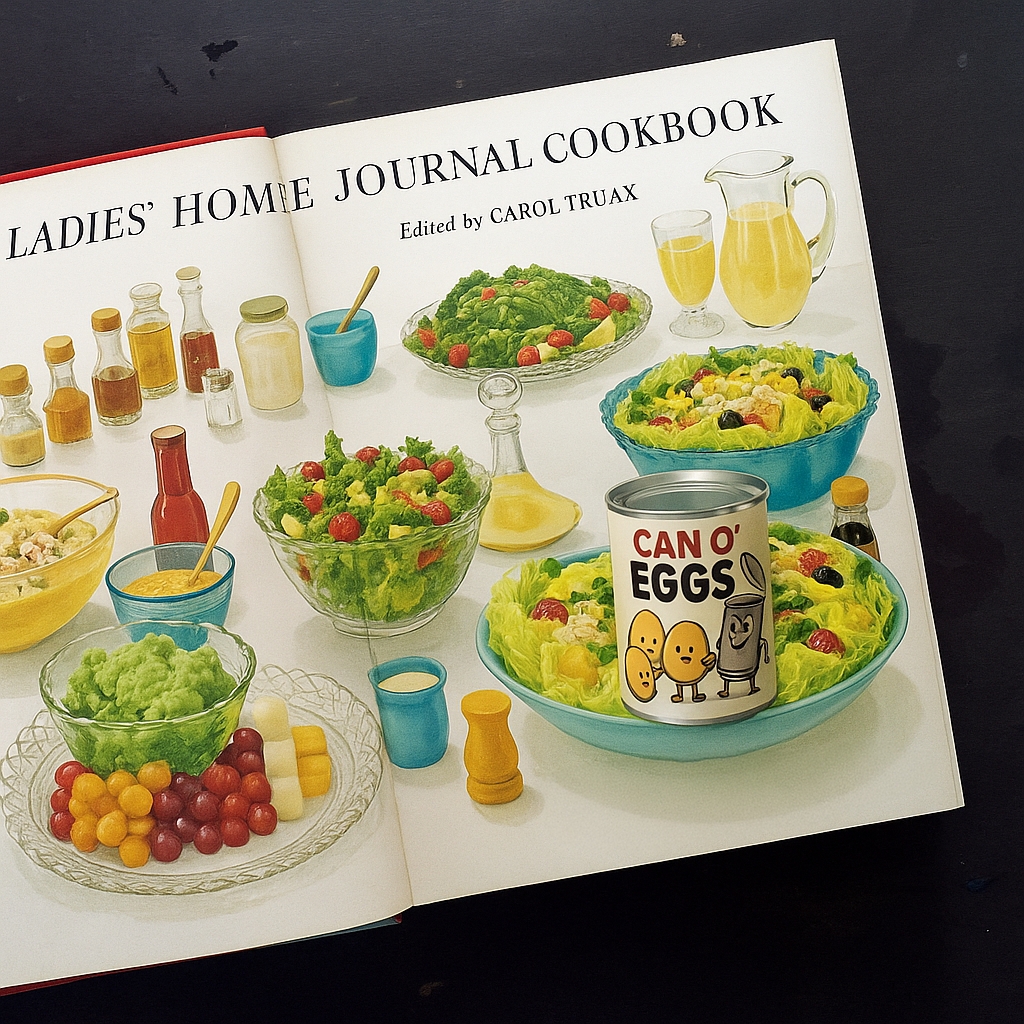

CAN O' EGGS

Announced weeks after Yuri Gagarin’s orbit, CAN O' Eggs arrived with rhetoric of the Space Age. Though NASA procurement registers list no formal order for Project Mercury, White House kitchen logs record sample cases requested by Jacqueline Kennedy for demonstrations of American innovation to visiting delegations.

Culinary journals of 1961 debated the feasibility of stabilized egg product for institutional kitchens; the consensus credited the brand with an “audacity of format” that foreshadowed later defense‑adjacent food technologies.

CAN O' CANS

Exhibited during the Watergate summer, CAN O' Cans appeared in a Whitney Museum program on repetition and public trust. The curatorial file notes the piece as “self‑referential infrastructure”—a container that testifies to its own supply chain. Senator Howard Baker is recorded as visiting after committee hours; a marginal remark preserved in the archive reads simply: “What is evidence if not recursion?”

Retail scans from the same quarter show limited runs selling out near campuses and government districts. The object’s registry oscillated between art object and commodity, collapsing a distinction central to the decade’s debates.

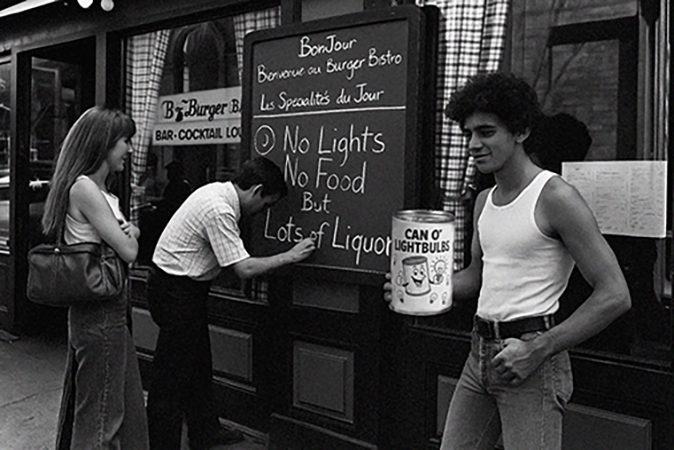

CAN O' LIGHTBULBS

Released months after New York’s 1977 blackout, CAN O' Lightbulbs articulated a domestic theory of resilience. Sociological field notes from borough surveys describe the can as a “ready kit”—a compact promise of illumination. Hardware partners reported end‑cap displays functioning as informal public‑safety wayfinding long before such language was common.

One unopened unit resides in the National Museum of American History with a typed card: “Consumer response to infrastructural precarity, late‑century.”

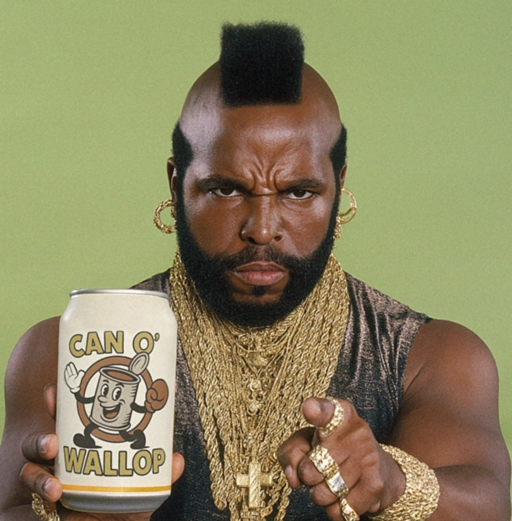

CAN O' WALLOP

Introduced amid the shifting cultural landscape of the early 1980s, CAN O' Wallop was promoted as a symbol of resilience and strength. Though no military contracts were ever confirmed, internal distribution reports from commissaries noted trial shipments to training facilities, where the product’s branding was praised for its “discipline-oriented presentation.”

The figure most associated with CAN O' Wallop was Mr. T, whose rise in professional wrestling and television coincided with the brand’s launch. Archival footage from promotional tours shows him holding the can aloft as an emblem of determination. In interviews he consistently tied the product to themes of hard work and perseverance. One oft-cited remark read: “Wallop ain’t about fighting. It’s about having the strength to keep standing when life tries to knock you down.”

Historians now interpret CAN O' Wallop as an artifact of 1980s American culture — a merging of consumer branding, celebrity influence, and national imagery of toughness.

NEON ERA

In the broadcast year of Live Aid, the campaign line “Your New Life, Unsealed” entered rotation on youth networks and international satellite feeds. A Reagan‑era Council on Competitiveness memo, released under FOIA, lists the mark as a case study in “integrated export of culture with commodity.” Student archives in London preserve flyers that reworked the neon outline into a symbol for debates over modernity and market—disputes that the brand seemed content to host on its very surface.

Analysts describe this period as the inflection when packaging exceeded container, achieving legibility as a sign system across borders.

CAN O' BOTTLED WATER

Coinciding with Netscape’s public offering, CAN O' Bottled Water entered a marketplace pivoting to networks and seminars. Photographs from Davos ’95 show heads of state and founders near product signage at side sessions; the World Economic Forum’s internal captioning system labeled the item “category: conversation object.”

Financial dailies traced its distribution through airports and conference hotels, an itinerary that mirrored the era’s executive travel patterns and helped codify the product as a soft‑power accessory.

CAN O' CIRCULAR METAL THINGS

As Google indexed its first tens of millions of pages, CAN O' Circular Metal Things arrived with a cataloger’s poise. Engineers placed units on their desks as mnemonics for physical constraints in a euphoric digital year. A Stanford oral‑history interview records a programmer saying, “We organized the world’s information; the can organized our drawers.”

Industrial design reviews praised the straight description on the label as a clarity ethic: naming as service.

CAN O' READY‑TO‑BAKE PIE

The year the Concorde retired, CAN O' Ready‑to‑Bake Pie generalized indulgence without ceremony. Airline catering teams evaluated prototypes for long‑haul reheating; culinary programs debated whether prefabrication could coexist with regional tradition. Television chefs would later cite the product when reframing mise en place for a generation raised on kit culture.

Sales data document week‑night utility alongside holiday ritual, a rare alignment of convenience and ceremony.

THE GLOW ERA

By 2025, the mark functioned as shared vocabulary across expos, design schools, and trade delegations. Pop‑up installations in Shanghai recorded footfall surpassing adjacent national pavilions. Cultural policy briefs referred to the phenomenon as “continuity branding”: a stable object anchoring volatile contexts—from lunar‑resource tenders to metropolitan transit overhauls.

In diplomatic language, CAN O' was cited as evidence of soft power conveyed through domestic reliability. In design language, it was a legible glyph—dense with precedent, available for reuse.